tl;dr

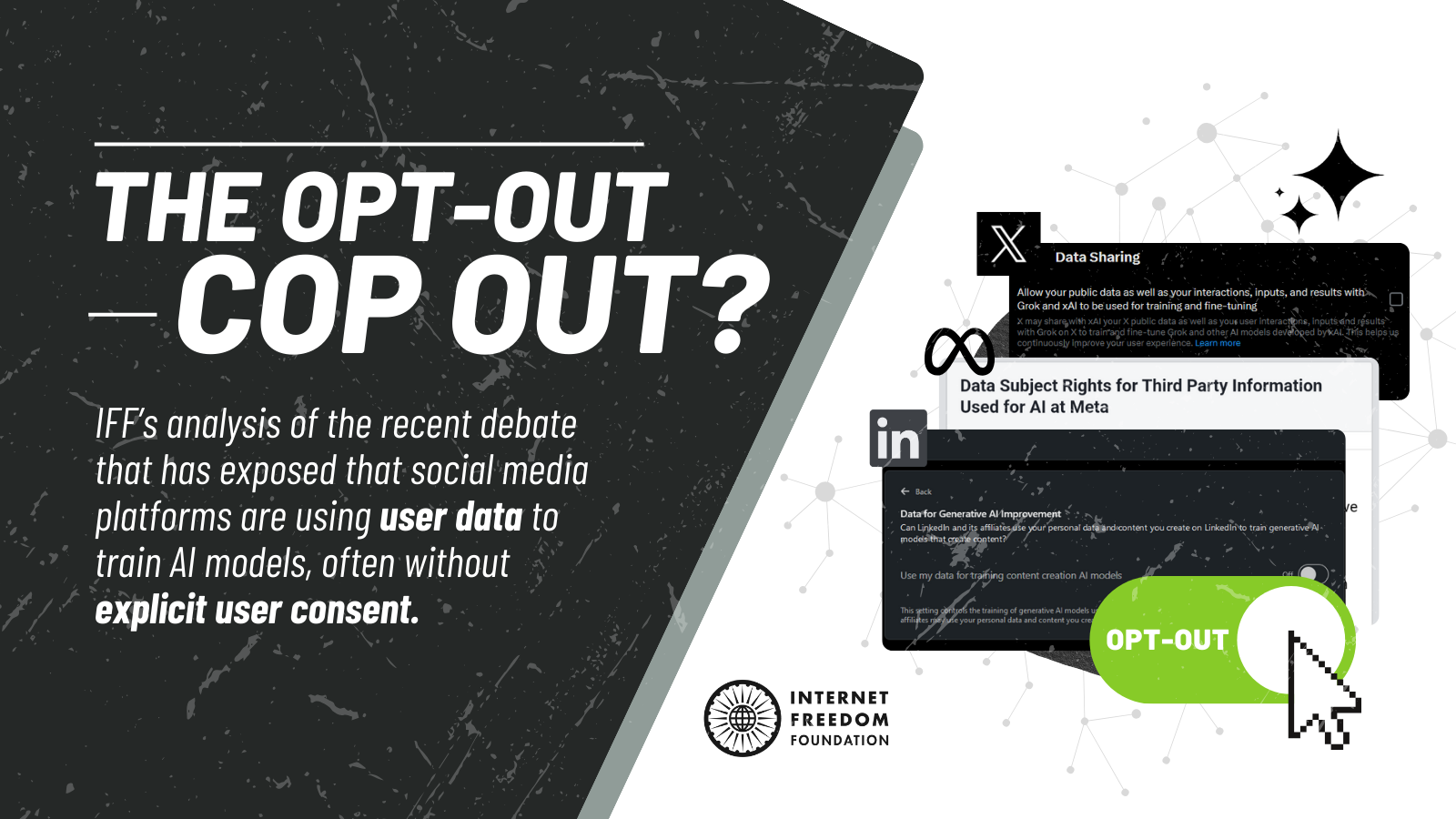

Social media companies have recently seen an exponential increase in the use of AI. The companies have been accused of scraping data from their users for training these AI models without obtaining explicit consent from their users. In our post, we discuss these concerns which are being raised in various jurisdictions and whether opting out is a choice given to us by the law.

Background

Beginning last year, there have been multiple revelations regarding social media platforms using user data to train their own AI models. In most cases, users were not explicitly notified that their data was being used to train AI models. In the past few months, revelations surrounding social media platforms using user data to train their AI models have led to public outcry.

In September 2023, Meta announced the launch of its new generative AI feature. The announcement states that considering generative AI takes a large amount of data to train, it used publicly shared posts from Instagram and Facebook, including photos and text, as data to train its generative AI models. In mid June 2024, Meta informed its users in the European Union (“EU”) and the United Kingdom (“UK”) that it has made changes to its privacy policy allowing it to use their information to develop and improve its AI products. This led to public opposition and complaints being filed before data protection authorities across Europe. In September 2024, before an inquiry by the Australian Senate, Meta’s global privacy director admitted to scraping data of Australian adults to train its AI models from as early as 2007 without providing an opt out option.

Further, in September 2024, 404media reported that LinkedIn introduced a new privacy setting saying that data from the platform is being used to train AI models, without simultaneously updating its privacy policy. LinkedIn has since then updated its privacy policy to state that “We may use your personal data to improve, develop, and provide products and Services, develop and train artificial intelligence (AI) models, develop, provide, and personalize our Services, and gain insights with the help of AI, automated systems, and inferences, so that our Services can be more relevant and useful to you and others.”.

In September 2024, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) published a report on the surveillance activities of nine of the largest social media and video streaming services, namely Amazon, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Snap, ByteDance, Discord, Reddit, and WhatsApp. The report highlighted that these platforms conduct extensive surveillance, gathering such vast amounts of data that they are unable to fully identify all the data points they collect or all the third parties with whom they share this information. Such incidents have shown that companies around the world have been silently scraping our data and training their AI models, which makes us question what we can do to prevent them from doing so.

Navigating the Opting Out Maze

The fact remains that in India, and most other jurisdictions barring the EU, social media platforms have not asked for explicit consent before using user data to train AI models. However, there are opt out mechanisms that social media platforms offer to allow users to halt access to their data by the platform for training AI models or any other purpose. Unfortunately, the opt out options mostly only let you stop some future data grabbing, not whatever happened in the past. Further, companies behind AI chatbots often do not provide details about what ‘training’ or ‘improving’ their AI models means in relation to your interactions. As a result, it's unclear what you are actually opting out of if you choose to do so.

While social media platforms do provide some vague opt out mechanisms for preventing companies from using your data to train their AI models, these are often not made plainly available and require the user to delve into the minute wordings of the application’s settings and permissions.

Let’s try to break down some ways in which you can opt out:

LinkedIn wrote on its help page that it uses generative AI for purposes like writing assistant features. We can revoke permission by heading to the Data privacy tab in your account settings and clicking on “Data for Generative AI Improvement” to find the toggle. Turn it to “off” to opt out.

The FAQ regarding its AI training states that it employs "privacy-enhancing technologies to redact or remove personal data" from its training datasets and that it does not train its models on individuals residing in the EU, EEA, or Switzerland.

- X

X, formerly known as Twitter, automatically activated a setting that allowed the company to train its Grok AI on users’ posts. X enabled the new setting by default. On X, you can click Privacy, then Data sharing and personalization: there you'll find a permission checkbox that you can uncheck to stop X's Grok A.I. model from using your account data “for training and fine-tuning,” as well as an option to clear past personal data that may have been used before you opted out.

- Meta

This year, Meta reignited its controversial plans to use the public posts of Facebook and Instagram users as AI training data. This resulted in both good and bad news. The bad news was that users in the US or other countries without national data privacy laws had no foolproof way to prevent Meta from using their data to train AI, which has likely already been done. Meta does not offer an opt-out feature for people living in these regions. The good news, however, was for users in the European Union and the UK, which are protected by strict data protection laws. They have the right to object to their data being scraped, allowing them to opt out more easily.

- Bluesky

Recently, social networking platform Bluesky said that, unlike other social media platforms, it would not rely on user content to train generative artificial intelligence (AI) models. However, it was pointed out by some users that Bluesky itself does not train AI models on user data, it just does not prevent others from using its data for training purposes. The company responded that just like other open websites on the internet, it is considering implementing a consent system for how other companies access Bluesky users' data. The proposed system would let Bluesky users indicate whether they consent to their content being used for AI training.

It also makes us wonder how AI chatbots are utilising our data where people are choosing to share personal information. Read more about this here.

Is opting out mandated by a law? Perspectives from around the globe

Social media companies do not tend to divulge much about their AI refinement and training processes, which makes it harder to make an informed choice about opting out. This raises the question: is opting out even mandated by law, or is it a choice that companies can make?

There are varying answers depending on the jurisdiction.

For those living in the United States, where online privacy laws are not as strict, companies can use public posts to train their A.I. This was noticed when Meta launched its new generative AI feature and technically were not required to notify users, and therefore users may not have realized that it had been training its A.I. with their public posts. So, if you want to opt out, you have to make your account private. Meta later also clarified that private messages between family and friends are not used to train its AI.

Those using Meta apps within the European Union, Britain, the European Economic Area and Switzerland were notified that they could opt out, according to Meta. These jurisdictions are protected by strict data protection regimes, users have the right to object to their data being scraped, so they can opt out more easily. For instance, under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), Article 14 states that individuals ought to be informed about the collection of their personal information (including the purpose of collection), even if this data has not been obtained from the individuals, i.e., inclusion of publicly available data. These and other obligations resulted in companies in the EU informing users about web scraping for the purpose of AI model training.

Now, coming to India, we have the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“DPDP Act”), which is yet to be operationalized. However, the DPDP Act excludes publicly available personal data from its scope. This means that AI entities scraping publicly available personal data for self-training may not be required to comply with data fiduciary obligations (e.g., obtaining prior consent). The DPDP Act does not require individuals to be notified about the collection and subsequent processing of data they might make publicly available on social media platforms. While more concrete jurisprudence is awaited on this, generating public awareness about the potential use of public personal data for AI modelling and training, deepfake creation, and possibly commercialization without users’ knowledge is becoming critical.

Considering that India has just enacted its first data protection law (the DPDP Act), its adequacy to deal with emerging challenges such as web scrapping ought to be considered. The very fact that even if the DPDP Act were in force, companies can get away with using user data to train their AI models is evidence that this law is not equipped to deal with emerging threats to individuals’ data. Any new law, but specifically those that deal with new technologies must be future proof and equipped to handle any new threats to the rights it seeks to provide. There is a significant need for India to deeply consider whether the DPDP Act is sufficient to protect the personal data of individuals. Considering that we are still awaiting the issue of rules under the DPDP Act, the real efficacy of the law remains to be ascertained.

Such trends exhibit that public social media posts are seen as fair game and can be hoovered into AI training data sets by anyone. Social media companies are conveniently relinquishing their responsibility by asking users who do not want their data to be used to set their account settings to private to minimize the risk. This implies that in practicality opt-outing settings mostly give the users an illusion of control. To counter this, data protection regimes around the world need to facilitate and build within themselves the right to object. The users need to have a clear method of opting out which is lacking in various jurisdictions presently.